Famed for his “Africa’s Monalisa” and Queen Elizabeth’s sculpture, Odinigwemmadu Ben Enwonwu, also known as Benedict Chukwukadibia Enwonwu (MBE), was a prominent African artist who achieved international acclaim in the 20th century. His work continues to inspire, and his five-decade career was a remarkable depiction of African art. Enwonwu was born in 1917 in Onitsha, Eastern Nigeria. His father, an Igbo traditional sculptor, introduced him to art when he was very young.

Before getting a scholarship to study in the UK in 1944, where he attended Goldsmiths College and the Slade School of Fine Arts, Ben Enwonwu studied fine arts at the Government College in 1934 (in both institutions, under the instruction of Kenneth Crossworth Murray, a British art instructor for the colonial government). He explored European art movements like Symbolism and Fauvism during this time. Enwonwu shows throughout his work that he can fuse the academically learned European techniques with his formative schooling in orthodox Igbo aesthetics.

Enwonwu also attended Goldsmiths and Oxford before finishing his postgraduate social anthropology degree at the London School of Economics. His encounters with racism in London contributed to his desire to pursue anthropology.

The scientific study of the many races, their physiology, psychology, traditions, and social interactions were made possible by anthropology. I suppose, in the mind of an intellectual, in addition to his art, this was the only way he could cope with the unfounded discrimination of the Empire.

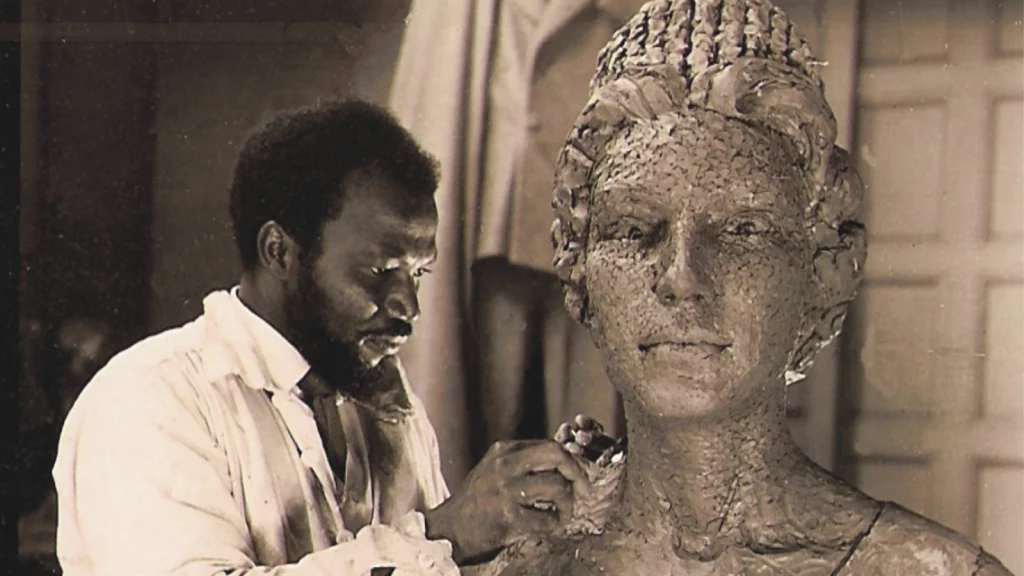

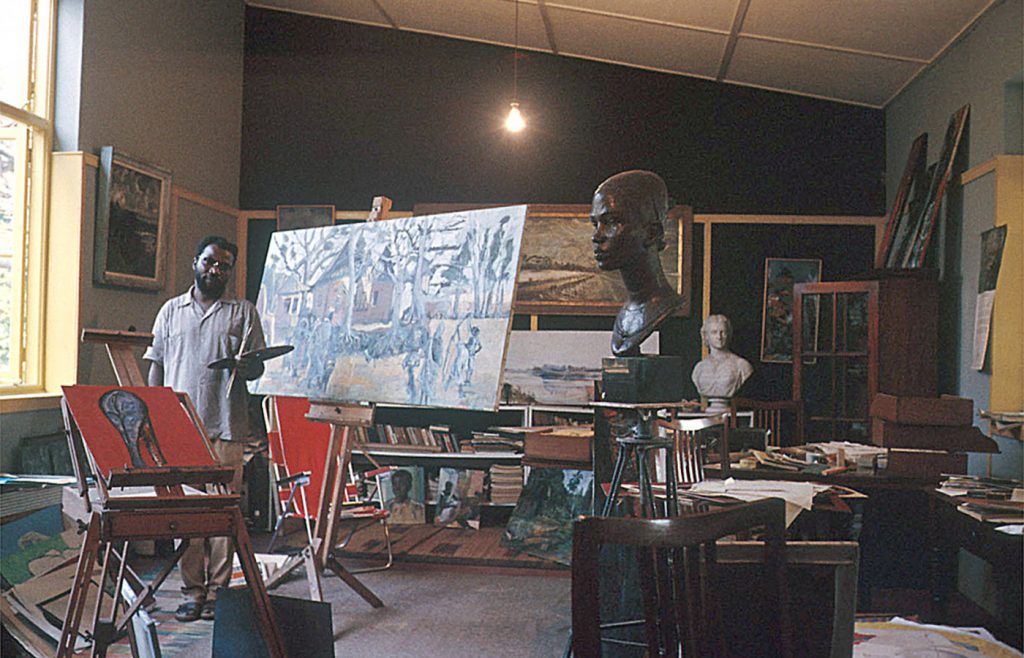

With his successful participation in a group exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery in London in 1937, Prof. Enwonwu’s career, initially as a sculptor, got off to a great start. This event was organised by his teacher, Kenneth Murray, who enjoyed presenting the works of his pupils. At the exhibition, his pieces stood out and received high appreciation from British artists and critics for being exceptional instances of modernist expressionism.

Enwonwu spent many years working with Murray before being hired to teach at the Government College of Umuahia. Murray was unhappy that the university decided to pay Enwonwu the same income as the other experienced lecturers, according to Sylvester Ogbechie, author of Ben Enwonwu: The Making of an African Modernist. This caused a chasm between the two men. Murray eventually quit teaching art at Government College, and Enwonwu took his place. He continued as an art instructor at many other institutions, such as Edo College in Benin City and a mission school in Calabar Province. He accepted a position as the Nigerian government’s art advisor in 1948.

The artist continued to work in Nigeria, where Ebony Magazine named him “Africa’s Greatest Artist” in 1949. Enwonwu received an MBE from Queen Elizabeth II in 1955 for his contributions to the arts, one of his many honours. When the Queen commissioned a bronze sculpture to be placed at the entrance of the Lagos Parliament Buildings the following year, he became the first African artist to get a royal commission. Queen Elizabeth II commissioned and posed for a portrait sculpture by Enwonwu during her 1956 visit to Nigeria. With Queen Elizabeth’s II death, it does elicit memories of Ben’s works, not to mention, the greater contribution of African art to Britain’s cultural history and the responsibility of an imperially complicated past. Enwonwu received the National Order of Merit in 1980 from the Nigerian government in recognition of his significant contribution to the nation’s arts and culture landscape.

Enwonwu added more fullness to the Queen’s lips by exercising artistic licence, sparking debate in the British art community. Despite the Queen’s open support for the sculpture, Enwonwu faced criticism for “Africanising” the monarch in some circles. The late master is credited with creating a Nigerian national style by merging indigenous traditions with Western methods and ways of representation, according to the Ben Enwonwu Foundation, established by Enwonwu’s son Oliver.

Ben Enwonwu’s artistic career, which stretched almost 60 years, was closely associated with one of the most significant moments in contemporary Nigerian history—the transition from a British colony to a newly independent African country. Upon its independence from the United Kingdom on 1 October 1960, Nigeria began to look for a new post-colonial identity. In 1968, the artist Ben Enwonwu was appointed the newly elected Nigerian government’s cultural advisor after becoming an advocate for a new national culture in Nigeria. Since the artist’s creations were even used to help Black liberation movements in Africa, Europe, and the US, Enwonwu’s fame spread widely.

Africa’s Monalisa

On the authority of Sotheby, in the years immediately following the end of the Biafran War, Enwonwu created some of his finest works, including this painting of Christine (“Africa’s Monalisa”) and the four known paintings of Adetutu Ademiluyi (also known as Tutu), a Yoruba princess from the ancient Kingdom of Ife. Christine is unmistakably a forerunner of Enwonwu’s famous pictures of the Yoruba princess, having been painted shortly before them. As stated in Sotheby’s Catalogue Note, Christine is particularly similar to Enwonwu’s most well-known painting of Tutu, whose whereabouts are currently unknown. Three paintings of the Ife princess Adetutu Ademiluyi (known as “Tutu”), painted by Enwonwu in a series in 1973, have been lost since 1975. 2017 saw the rediscovery of one of the three paintings in a London apartment. In a Bonhams auction, it brought in £1,205,000. One of the artist’s three portraits of Tutu is a Nigerian national treasure and is regarded as a symbol of peace between the government and Biafran rebels post the civil war.

Despite the fact that Enwonwu is highly recognised for his portraiture, works of this calibre are extremely hard to come across.

As oil on canvas, Christine is a product of the friendship between Christine and her husband, Elvis, and the artist. Christine was renowned for her grace and dignity and had the intrinsic ability to remain calm and motionless for however long the artist desired. Christine’s fleeting beauty is captured by Enwonwu’s free brushwork and vivid oil. Her long neck, radiant skin, curved lips, and exquisite smile are all depicted, which attests to the sitter’s tenderness and charm. The painting captures Christine’s passion and poise, which is evidence of their mutual trust and cooperation.

Consequently, why is she called “Africa’s Monalisa”? It emanates from the dignified presentation of her figure, translated through her exemplar of a regal posture and authority of a nobility. Christine assumes the room, elegantly; there is a subtle emotion conveyed through her gentle restrained smile (some would say Monalisaesque smile) and a sense of ease in her eyes that exudes to the viewer. This regal and dignified attitude is accentuated in both Christine and Tutu since both sitters share a spellbinding frontal glance and have their midsections positioned similarly to classic Western paintings: outward and angular.

A backlight can also be seen on Christine. The luminous quality of the light in the portrait highlights the distinctive features of the subjects, primarily their longer necks, a trademark of Enwonwu’s art. The piece has a halo of light that gives Christine a delicate, yet iridescent and ethereal shine.

What we learn from history is that Christine had a deep appreciation for the various cultures she experienced. She wanted to express herself stylistically by wearing the traditional clothing of the region. This is further supported in the painting when she is shown to be married and is identified by the beautifully tied headscarf known as a gele. Christine was not born in Lagos, Nigeria, but her outfit demonstrates her connection to the country and her strong admiration for West African tradition. I suppose this is the story of many artists in the continent, whose works echo far and wide, presenting some sort of way back home for the coloured peoples of the continent in different parts of the world, and vice versa. This is the story of Bolingo, a platform whose mission is to champion Afro-inspired art.

The Third Space in Art History

Ogbechie notes that his work [establishes] the third space in art history whose character and limitations are at variance with art history’s discriminatory discourses of modernity and its imposition of the modern artist-subject as a white, Western European male. The recognition of his bronze statue of the Queen demonstrated how, as an African modern artist, he used his practise to create a new type of modern art with representational ideals and conceptions of artistic identity that were distinct from the traditional art-historical storyline of European modernist practise.

The world has been fascinated by African art for ages. Colonialists took a deep interest in African art when they arrived in Africa centuries ago, and many works were plundered. Hence the numerous collections that are still on display in museums around the globe. This art mostly consisted of conceptual representations of everyday life, such as African culture and daily life, and frequently showed the riches of the natural surrounds. Many of the important religious and ceremonial works of art in this collection have never been returned to their original caretakers.

However, if so many collectors have a passion for it, why has it been criminally undervalued for so long? We must consider the forces at play on the African continent to respond to this topic. It’s not that we are not cultured, indeed, we are, vastly. One of these countervailing forces is poverty. Given the severity of their poverty, it is unlikely that Africans would choose art over food. This has caused a void that artists must fill on their own because there is no active middle class to support them. Nevertheless, things are changing.

First, is the increased acknowledgement of African artists. Increased auction sales serve as a sign that African artists are becoming more popular in the international art market. These artists are still a small part of the industry, though. Despite all the excitement, the global art market still only includes a modest amount of modern African work.

Worldwide sales of African art represented less than 4% of the global market, as per “The Art Market 2018” report. Since there are more art buyers in these developed countries, the United States, China, and the United Kingdom continue to control the market.

Second, a rising middle class in the continent as reported by the African Development Bank, which estimated that 34% of the African population then had risen to the “middle of the pyramid”, about 300-500 million people. Nonetheless, the middle-class picture in Africa remains complicated given the intricacies of national and household incomes.

That said, the prospect of African art remains a positive one, steeped in the massive talent in the continent, an undervalued market, and the cultural zeitgeist happening, specifically with the Afrobeats genre of music.

African art is in vogue right now. Never before has there been such a consistent and focused focus on modern and contemporary African art. The demand for African art has increased considerably over the past few years both domestically and abroad. In particular, there has been tremendous global attention. African art is far too frequently ignored and devalued in a setting of a rapidly expanding market. A genuine disquiet for the vast group of enthusiasts and collectors of African art.

In the past ten years, and more significantly in the past five years, a sizable number of African works of art—even those from the early 20th century—have made their public debuts. Yes, there is a glaring knowledge gap regarding these works. Bolingo is at the heart of this revolution, positioned to power the inexorable nascence of this market.

Ben Enwonwu’s embodiment of the philosophy of Negritude, which is regarded to be closely related to the Harlem Renaissance, glorified Africa and blackness. The African philosophy of Negritude quips Enwonwu, (1968) established the sort of enlightenment that typified the African spirit and mind.

Enwonwu was not only a well-known painter and sculptor but also a respected author and art critic. Ben Enwonwu was regarded as one of the most esteemed African painters of the 20th century by the time of his death in 1994 and would continue to be so.